For an introduction to Mark McDonald’s works as a former Journalist and now a book publisher, click on the link that follows.

INTRODUCTION BY BILLY DALE (squarespace.com)

Royal Moments in Time- By Mark S. McDonald Sr.

“The true measure of a man is how he treats someone who can do him absolutely no good.” – timeless wisdom, famously written in 1978 by syndicated advice columnist Ann Landers.

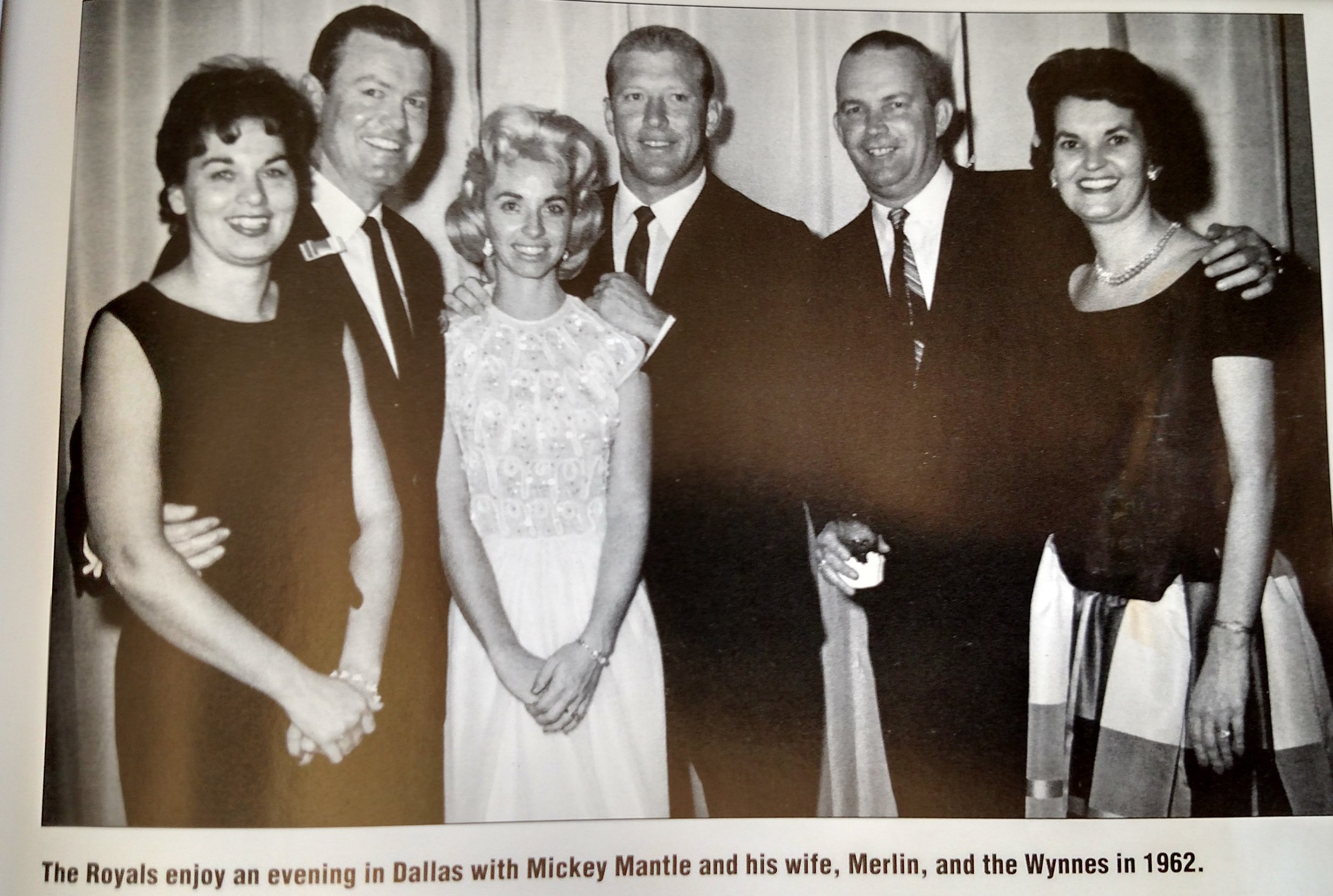

Mickey Mantle and DKR

Some years ago in Dallas, the late and legendary Texas Longhorns football coach Darrell K. Royal was enjoying a social gathering with friends when he happened into another notable sports figure – Mickey Mantle.

Royal instantly recognized Mantle as the New York Yankees slugger, but there was more: While DKR had come out of tiny Hollis, Okla., to star in the late 1940s at Oklahoma University, Mantle was another small-town Okie from Commerce who was crushing it, in his own game, in his own way.

Brought together by time and happenstance, DKR puts his hand on Mantle’s shoulder and asks why he chose baseball rather than joining him in Coach Bud Wilkinson’s backfield at OU.

“Coach,” Mantle says, “back then, you weren’t Darrell Royal.”

DKR can only smile. “And you weren’t Mickey Mantle either.”

Back in 1949, when DKR and Mantle could have crossed paths but did not, the “Commerce Comet” was a high school shortstop who signed with the New York Yankees. Mantle’s baseball feats became legendary -- a three-time American League MVP, played in 12 World Series and hit 18 Series homers en route to the Hall of Fame.

DKR- the early years

For his part, DKR’s Longhorns won 11 conference titles, plus three national titles, as he plied the University’s considerable assets and built on them. It is beyond the playing field, however, where Royal left his mark.

In 1961, Royal’s teams began to display the spreading horn creation designed by DKR and Rooster Andrews for the Longhorn helmets. Years later, the UT-Austin brand was named by Sports Illustrated as the No. 1 logo in college sports. Today, the extended index finger and pinkie “hook ‘em” is recognized worldwide.

The thing is, DKR was always and forever Darrell K. Royal.

Three DKR moments, occurring decades apart, tell us far more about the fabric of his character than his 167-47-5 won-lost-tied record ever will. Looking back, three intensely personal moments connect a remarkable man to a legacy that might never be duplicated.

#1 My first glimpse of DKR greatness

The scene is a warm September night in 1962, set at a football stadium in Houston where my mighty Spring Branch Bears play … for playing in the local youth league, we youngsters get into games free … Tommy Evans, a grade-school teammate on the Indians as we were called, has no way of knowing he is bound to sign with Gene Stallings at Texas A&M. He only knows he is puzzled by what he sees walking up the aisle.

I well knew Coach Royal from the wing-T offense we ran at Landrum Junior High. I cannot tell you where my pickup is parked, but I can still recite the calls we linemen made for our double-team blocks 60 years ago.

Right away, from the sports page of the now-defunct Houston Post and the occasion when network TV would show Texas on our flickering black-and-white set with the rabbit ear antennae, I recognized the figure walking up the stadium steps. Coach Royal’s features were grim and tight, his manner subdued.

“Who is that?” Tommy says, gawking at a square-jawed man in a white dress shirt and black ribbon of a necktie.

“Ya dope, that’s Darrell Royal. Coach of the Texas Longhorns.”

I elbow Tommy in the ribs. “Don’t point at him.”

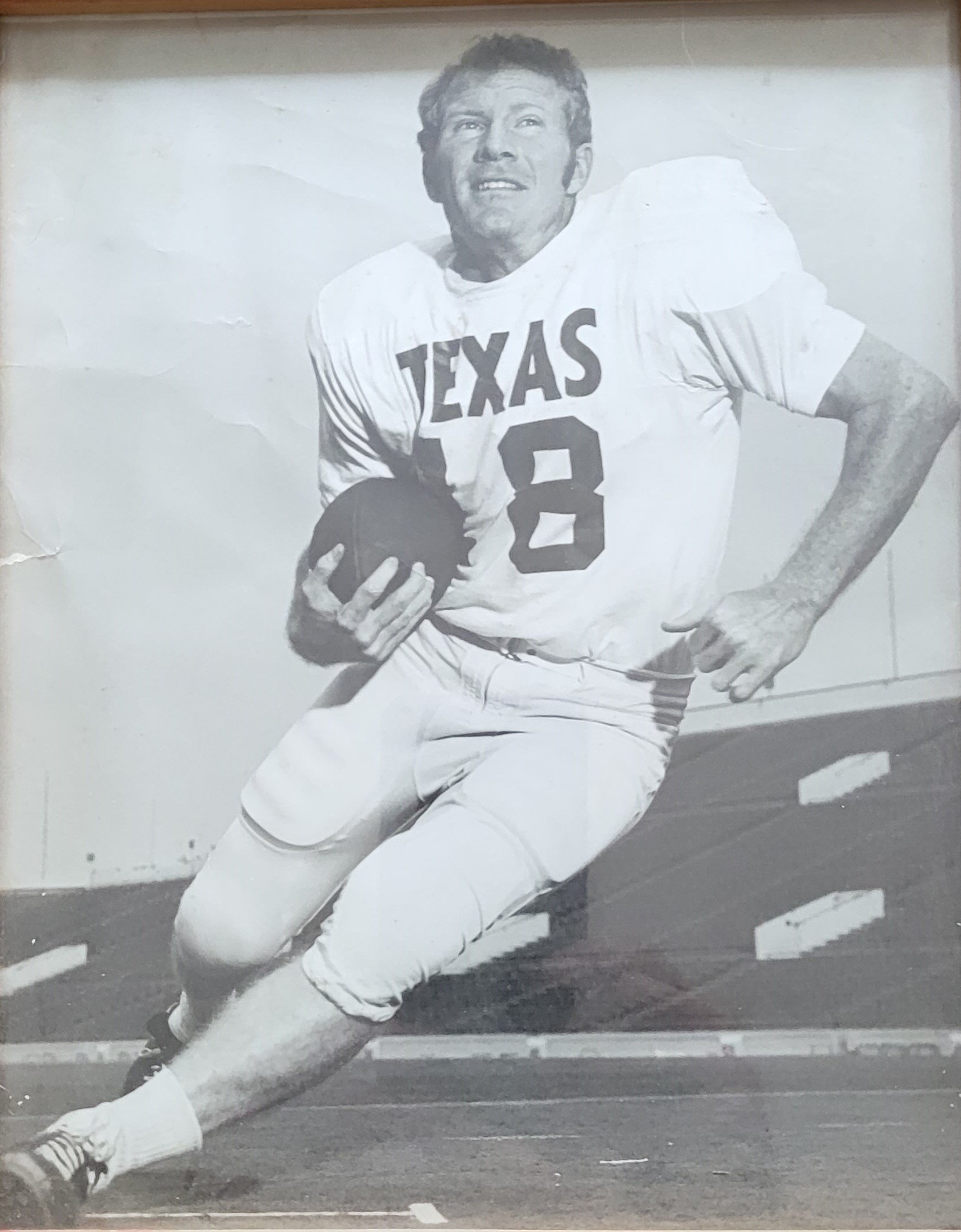

Royal and his staff would later visit Spring Branch to recruit a shifty halfback named Chris Gilbert and a sturdy center named Jim Achilles. In 1966, a clever 5-8 redheaded quarterback named Donnie Wigginton led SB to the state final before losing to Emory Bellard’s San Angelo Bobcats. Donnie was the QB on our Peewee Indians team, so small wonder we lost exactly one time in three years. But this was ’62.

Gilbert was still in junior high, said to be driving the fastest go-kart in the neighborhood. On the eve of Texas’ 1962 season opener, Coach Royal boarded the entire Texas team on a bus and rode from Austin to Houston. Why?

#2 My second glimpse of DKR greatness

Here is a link to Reggie’s story https://texas-lsn.squarespace.com/reggie-grob and https://texas-lsn.squarespace.com/1962-reggie-grob

Reggie Grob, a lineman from SB, has just died of complications from heat prostration, 17 days after collapsing during the Horn’s first practice. DKR and the team have come to our neighborhood to honor the Grob family and salute Reggie’s memory.

This is Friday, mind you, only hours before the Horns are to play a quality Oregon team featuring Mel Renfro, bound for a 14-year career under Coach Tom Landry, a Longhorn himself, and the NFL Cowboys.

Purely from the football standpoint, the late Reggie Grob might not have meant much to some coaches. He was, after all, a walk-on lineman and, at 197 pounds, no giant by Southwest Conference standards of the day. Given the grim turn of events the past two weeks, some coaches – especially today – Royal might have sent an assistant, an intern and stayed in Austin for final preparation. Not Darrell K. Royal.

He and his team made the trip, and returned to Austin on short rest. Linebacker Pat Culpepper would wake up the next morning and make 14 tackles, Duke Carlisle seven, and Tommy Lucas six. All told the Horns managed just eight first downs, but before a Memorial Stadium crowd of 50,000, they overcame seven penalties, two lost fumbles, and an interception in an unlikely 25-13 victory.

DKR and his wife Edith would come to know grief when two of their three children died after separate car accidents. Reggie Grob was part of it, but in the darkness, former Longhorn Sports Information Director Bill Little found a ray of sunshine in a broader message. In 2001, he wrote this:

“While Oregon worked out in Memorial Stadium, the Texas team drove to Houston for the funeral of Reggie Grob.

… In his passing, Reggie Grob did something immeasurable for the living … every athlete or wanna-be athlete learned something the day Reggie Grob died. Trainers and doctors, led by the American Medical Association, began immediate research on the effects of heat on the human body … practice routines were strictly governed by schools throughout the country, and every single person … knew of the dangers of heat exhaustion.

Texas did beat Oregon in a tough game that next day, but it really didn't matter. That's in the record book. It was Reggie Grob who mattered. In a very real sense, his death meant that thousands and thousands have lived. Out of tragedy, he gave us all a gift. And that's why he's a legend.”

Grob’s body temperature, in the boiling sun of a late-summer day in Austin, had reached 106 degrees. Coaches and trainers have since learned that a water break for players is not a sign of weakness. It means survival.

Three years after the death of Reggie Grob and the likes of SMU center Mike Kelsey, researchers developed a carbohydrate-electrolyte liquid tested on the University of Florida’s freshman football players. We came to know it as Gatorade.

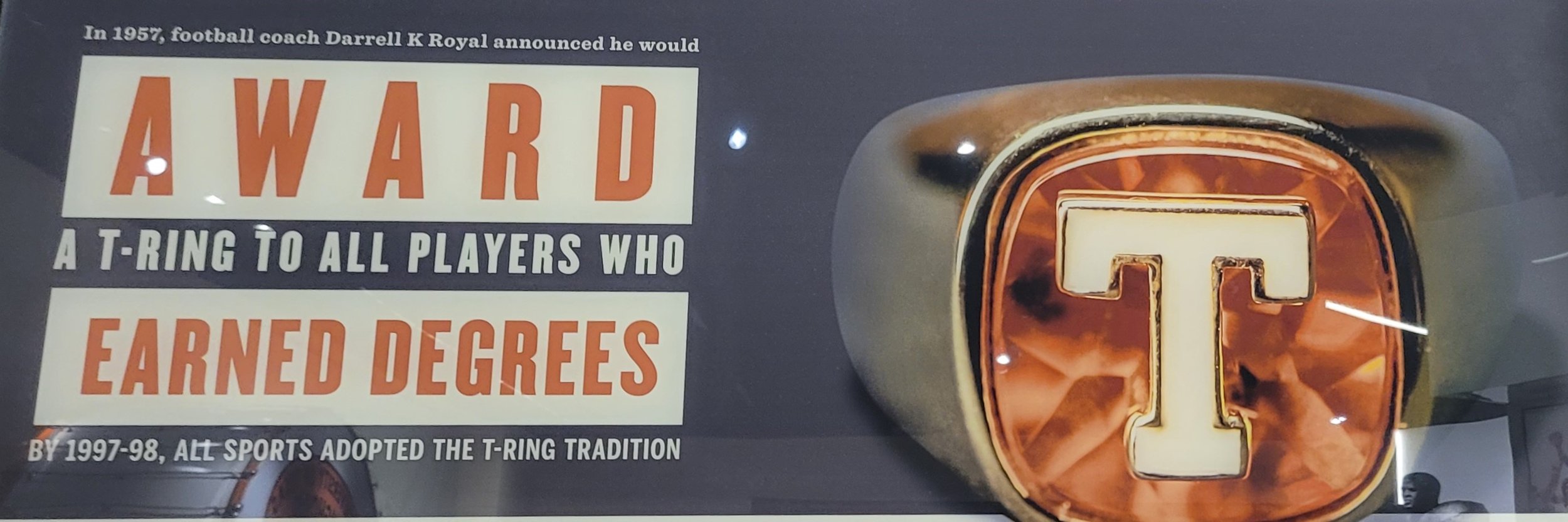

DKR touch of class starts the “T” ring tradition

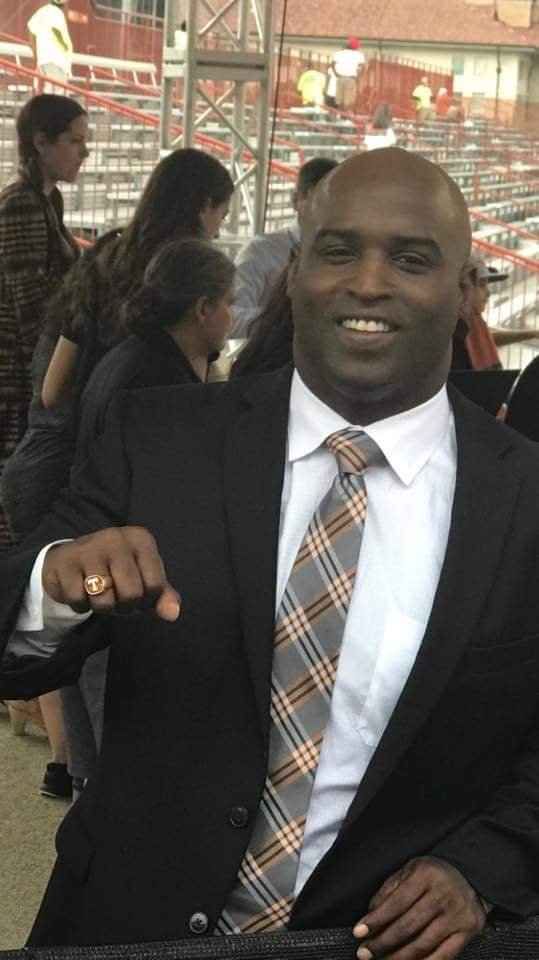

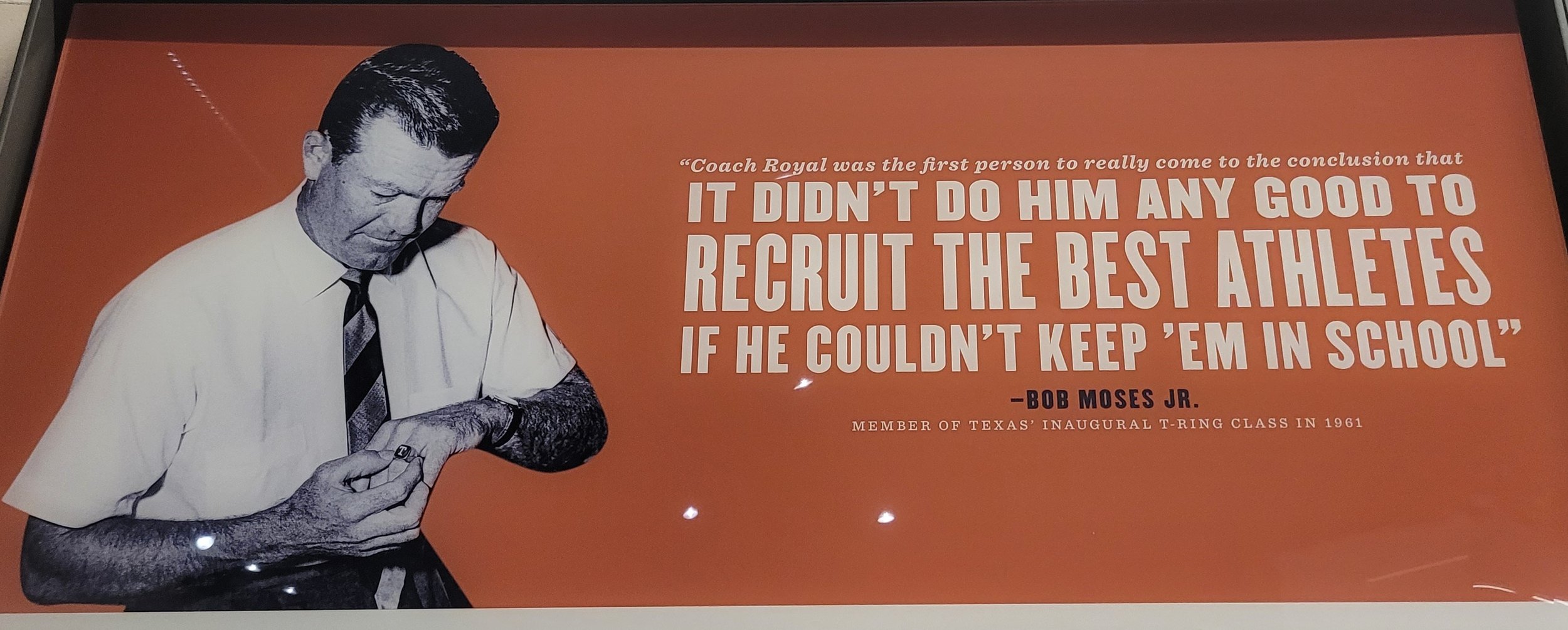

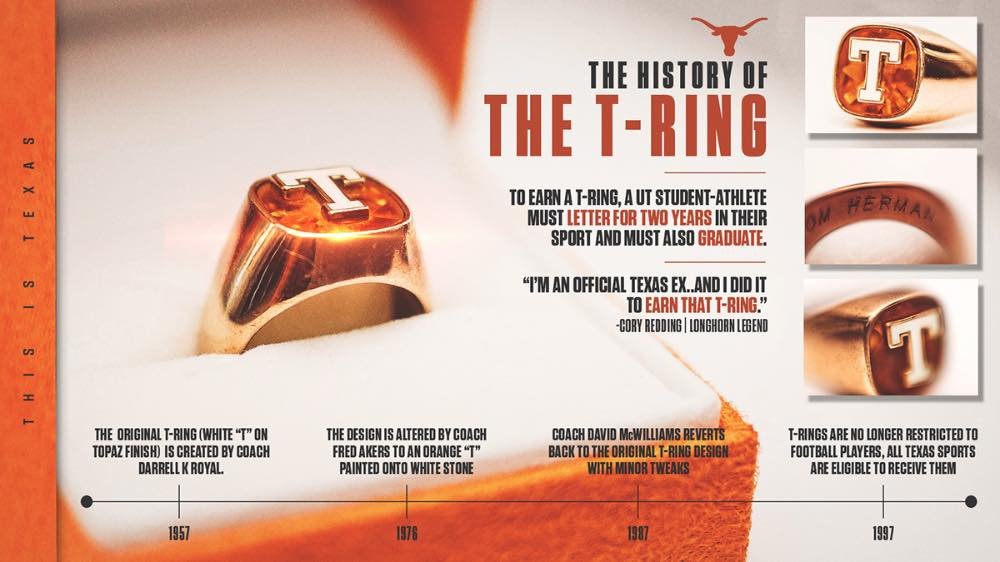

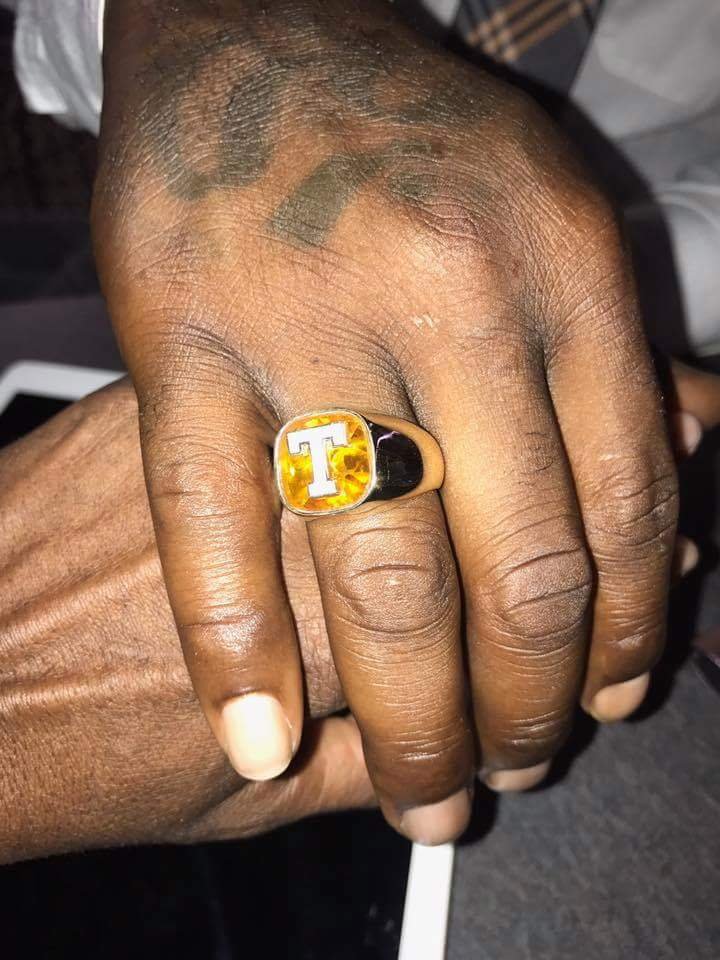

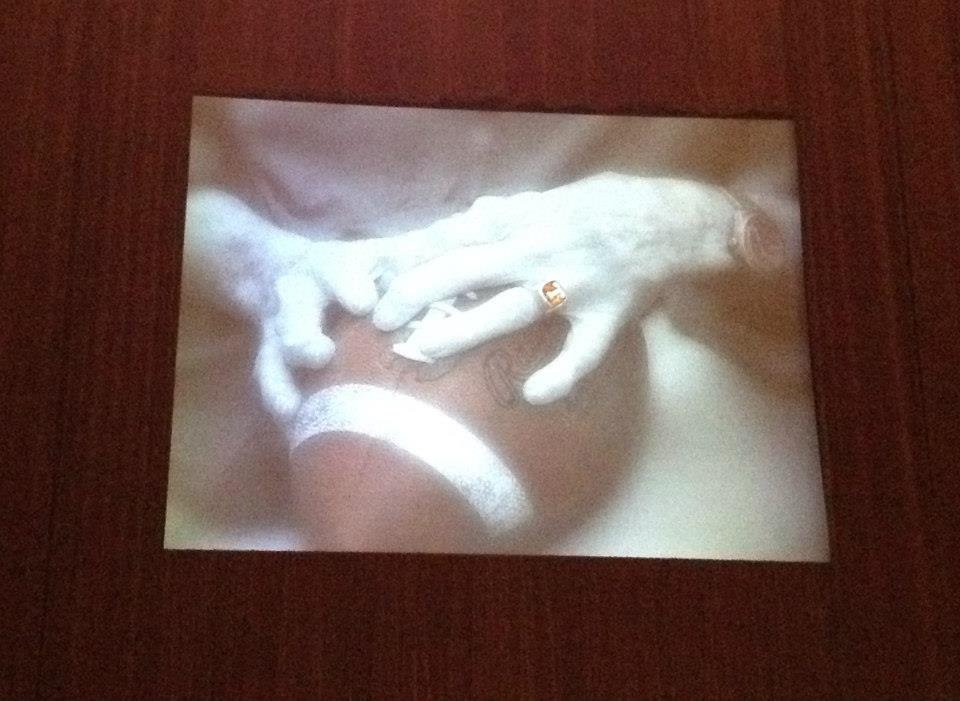

Here’s another touch of class from Royal that sprang out of a good man’s heart to outlive him: In 1957, DKR came up with a then-unique way to honor his senior lettermen. Players who finish their eligibility at the Forty Acres and complete degree requirements are awarded a “T-ring” to symbolize dedication and commitment.

A legit T-ring cannot be bought, at least not a real one. They are not for sale at any price. A T-ring must be earned.

Below is a montage that tells the story of the T-ring. Click on the arrows on the sides of photos to move from one image to the next.

DKR launched the tradition with his own money to salute young men who could no longer do him any good, at least on the field. Women athletes who also earned T-rings have long taken it to heart, too.

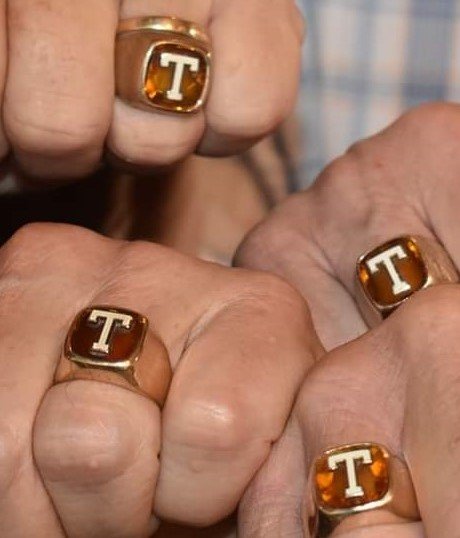

Many ex-lettermen and women hold the T-ring so dear they keep it locked in a safe deposit box. Even well into his 50s now, my son Turk (Mark Jr.), his fingers disfigured after years of grappling rivals hand-to-hand, knows exactly where his ring is stored, and he’s not saying where. Some Longhorns display their T-rings in a trophy case mounted on the mantel in their dens.

#3 My Third Glimpse of DKR Greatness

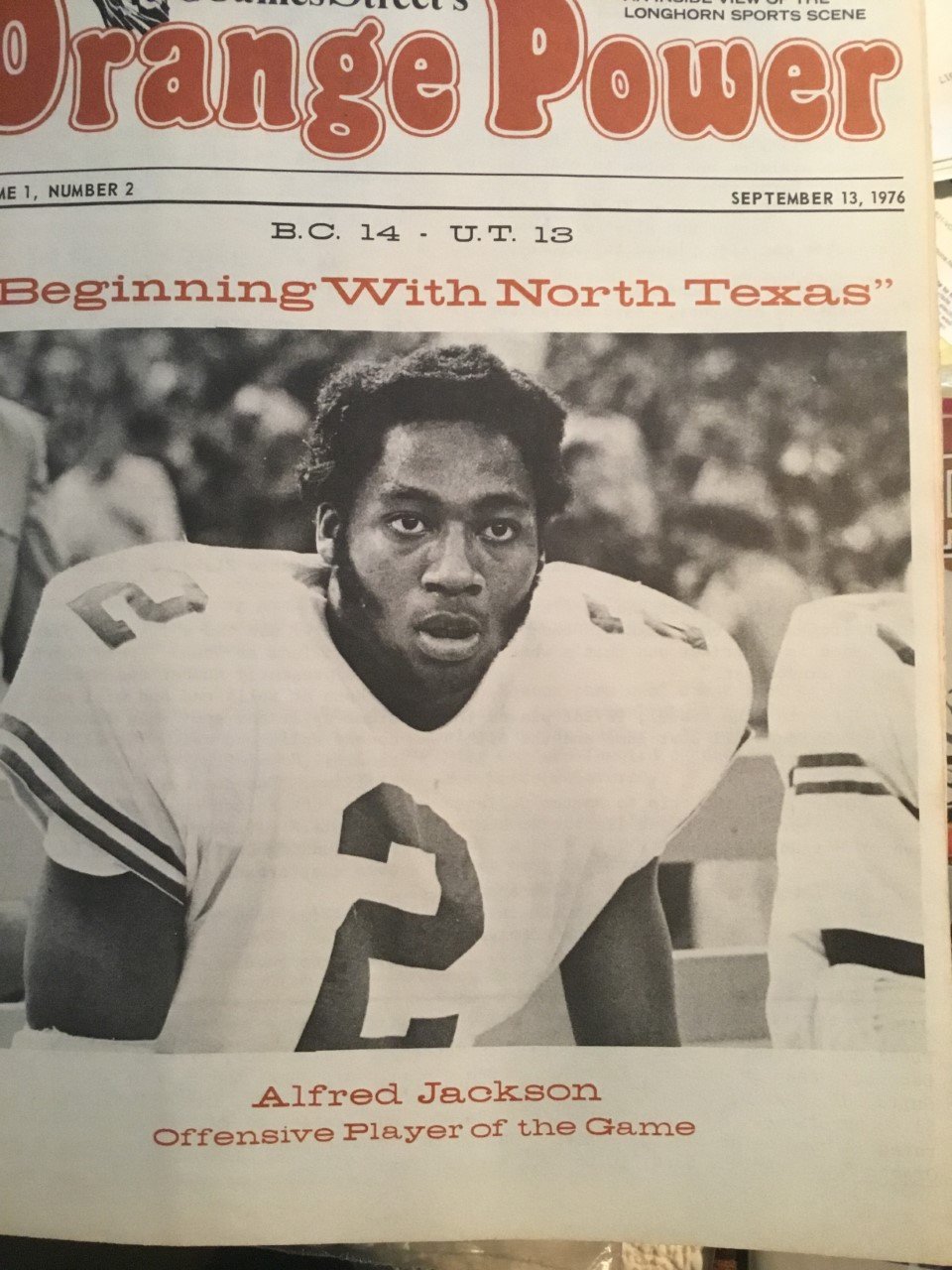

It is December 4th, 1976, in Memorial Stadium, where Texas has just beaten Arkansas, 29-12. Not so long after the epic 1969 Big Shootout between No. 1 and No. 2 for the national title, this was a pillow fight.

The Texas roster was not barren, not with the likes of a young running back named Earl Campbell, placekicker Russell Erxleben, receiver Alfred Jackson, defensive backs Ricky Churchman and Raymond Clayborn, plus long-time pro-linemen-to-be David Studdard and Brad Shearer. But in a season in which Texas lost to Houston, 30-0, something was missing. And Orange bloods knew it.

Just after losing to A&M 27-3, before 75,000, Austin attendance had slipped to a season-low 49,341. By the fourth quarter, whispers had become more than that. Royal, after 20 seasons, stepped down as the Longhorn head football coach.

Football history of this day rarely comes with such a snug fit.

The Story of Mark McDonalds post-game interview with DKR.

Both Royal and Arkansas Coach Frank Broyles – each with a 5-5-1 finish -- chose this evening to hang up their headsets. Royal and wife Edith had often vacationed with Broyles and wife Barbara, playing racehorse golf … hit the ball, chase it, hit it again, with no waiting for the snap count. They talked about golf and current affairs, never football. The women avoided football, too, focusing on family events and holiday gatherings. Now, two giants on the Mount Rushmore of college football were jumping in the same cart and headed for the first tee. ARTWORK BY Bill DeOre

So there I am, in the Memorial Stadium press box, with 50 minutes to file my game story and locker room coverage. To share the deadline load, the Abilene Reporter-News might have sent an extra hand, but no. Our sports staff was stretched tight across the drumhead. The ARN, in addition to the Little Southwest Conference that included Odessa Permian and my alma mater, Midland Lee, covered sports played at 60 Big Country high schools.

My story, and those of my colleagues, were delivered to readers from Big Spring on the west nearly to Wichita Falls on the north and Lubbock up yonder. Texas SID, the late Jones Ramsey, and his capable assistant, Bill Little, were top-drawer pros. Along with a capable staff, they provided all quotes and decimal points our paper could hold.

Even so, Darrell Royal has just retired, and there was zero time to tie the story in a neat ribbon. You could hear my gag reflex from Austin all the way to our Pine Street offices in downtown Abilene.

As the final few minutes of the game clock wound down, I filed a brief and forgettable game story ledger to answer the four W’s – who, what, when, where, and why. Next, I hustled to the Texas locker room in the shadows under Memorial Stadium’s west side. From there, I started looking for Royal.

Little did I know, while I pestered students for their worldview through the bars of a facemask, Royal held court for reporters. I missed it all. On the only day Darrell Royal would ever retire from coaching, I totally whiffed.

Normally, I would never have dreamed of intruding into the safe haven of the coach’s locker room. But DKR was retiring. Time was short, but this story was taller than a sequoia. I took the dive.

Beneath an empty stadium were scattered popcorn, pigeons, and me. I found the right door, knocked, and entered the inner sanctum. I saw a rather Spartan row of benches and the usual metal lockers you would see at your local YMCA. A lone remaining assistant brushed past me – Spike Dykes, whom I had known from our shared time in the cactus country – leaving me alone with Royal.

By this time, I was six years deep into a lukewarm career that began at the El Paso Times ($90 a week, thank you very much). You would think I knew my way around a notepad, but I was totally unprepared for what came next. Pulling on his boots in no particular hurry, Coach Royal was beyond generous.

One by one by one, the coach answered each of my questions as if he already knew what my readers wanted to know. No rolling of the eyes, no sarcastic sighs. Instead, he graciously gave me ten precious, uninterrupted minutes that he was not duty-bound to give.

His answers would not bring world peace. My interview would not bring Royal a hot new recruit from my paper’s circulation area. Too late for that. The coach was retiring.

Instead, Royal kept it simple. He donated his time because he was fronted by a reporter he knew to be in a pickle. Sweating grateful bullets, I hustled back up to the press box, where I was the last writer to peck out yet another Pulitzer loser.

My deadline account would never make a ripple. It was a speck of sand in the desert. Certainly the high-profile Royal would never remember it from the hundreds, thousands, of interviews he had given.

But to this day, I cling to sepia-toned images of a medium-sized fellow – a big man inside – giving something to someone who could do nothing for him. It’s an old movie, replayed over and over. It is Darrell K. Royal, still coaching me up with a life lesson never forgotten.

David Allen- says:

Billy Dale as the last equipment manager in the locker room that night in 1976, I waited until Mark McDonald finished his interview with Coach Royal. I wanted to get coach’s autograph on the game program for the Arkansas game that night. Of course he obliged, thanked me for being a manager, and headed for the door.