HAPPY FATHER’S DAY FROM pROFESSOR LARRY CARLSON

HAPPY DADDY’S DAY

Larry Carlson ( lc13@txstate.edu )

If you grew up the way I did, your dear old Dad got an array of socks and handkerchiefs each year on Father's Day. My older sisters and I didn't need to do much or buy much. Maybe now you're the happy recipient of a Home Depot card or a book each June. Father's Day just ain't in the same league as Mother's Day when it comes to pressure, care, and creativity.

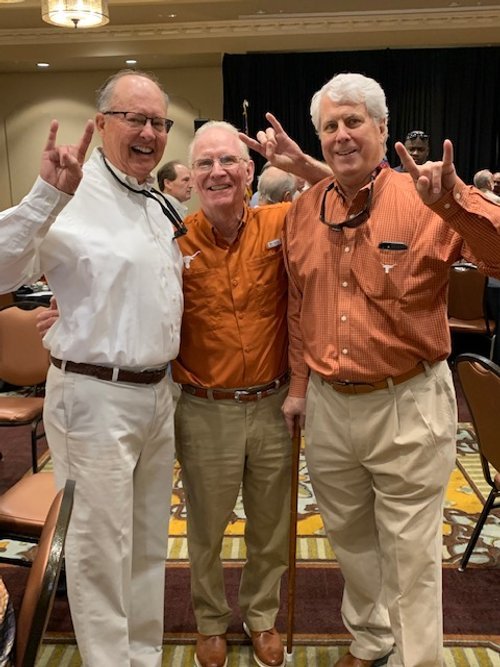

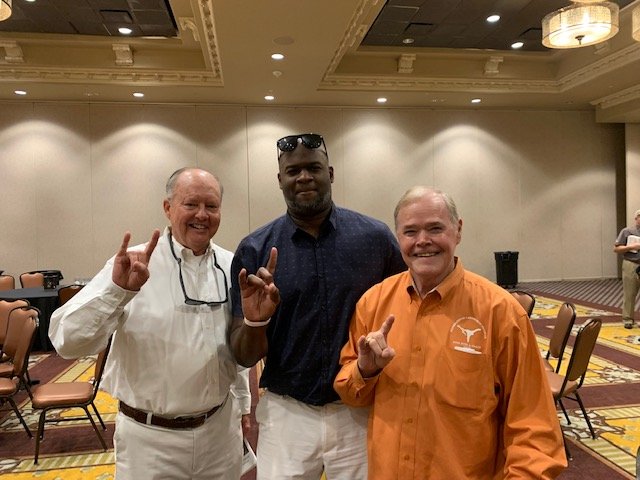

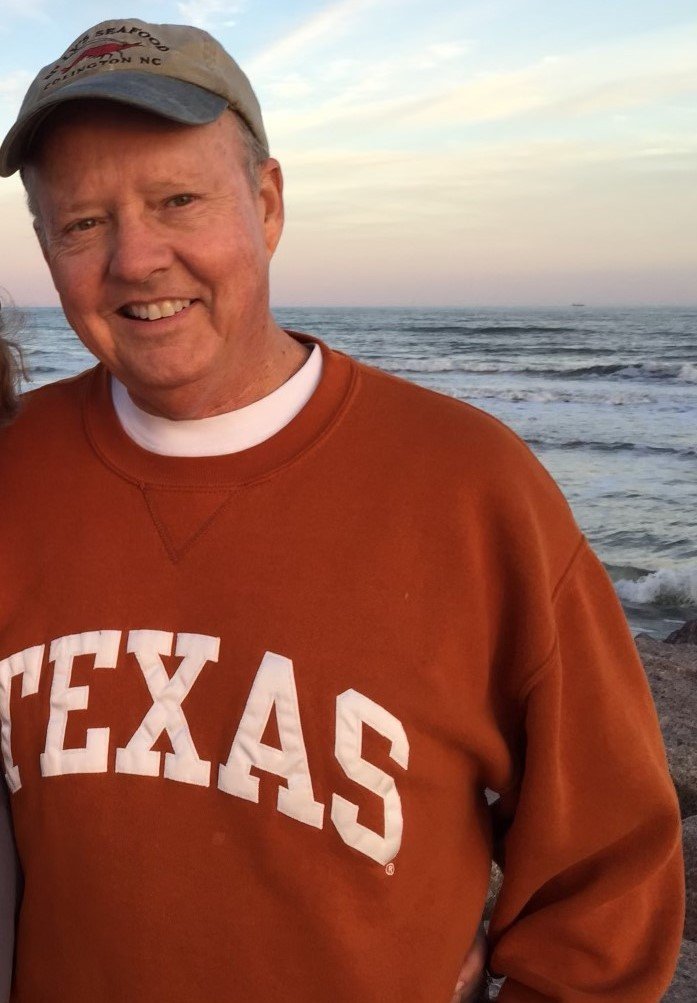

Daddy liked it when I made him a card; they were usually Longhorn-themed. A good Aggie joke was always a hit. Like a zillion others who reside in Longhorn Nation, I was brought up by my father to love the Longhorns. To reverently stand and sing The Eyes of Texas, to proudly flash the Hook 'em sign, and to eagerly anticipate the beam of an orange tower after yet another Texas win.

The devotion of Longhorn fans is most frequently borne of family ties. It's something not all schools, not all athletic departments can rely on. Not to short any of the UT moms out there, but let's face the sheer numbers. For decades upon decades, at virtually all schools, the enrollment was mostly male.

My dad had a story that was typical for his era. He was born in the early 1920s and raised during The Great Depression. The toughest of times. It forged a wealth of grit and determination amid a common set of hardscrabble upbringings and austerity if not abject poverty.

Born in Taylor to a Swedish immigrant and a woman of Czech descent, little Everett Carlson was quickly part of a home broken by divorce, which was uncommon at the time. He was sent to be raised by his Uncle Sam and Aunt Annie on a farm just outside Elgin. Daddy was permanently left without any real father figure when his dad died in an auto accident. I have a picture of my Dad, a skinny youngster of thirteen, alone and somberly staring at a hole in the ground, the grave of Oscar Carlson from Sweden. It's the saddest picture I have ever seen.

But Daddy was a smart kid who, at 16 1/2, was Elgin High's class valedictorian for 1939, paving the way for him to attend The University of Texas on an academic scholarship. He tried out for the UT tennis team and was not intimidated. But as he later told me, the coach didn't like all the English and spin that the tall, thin teen tried to employ on too many shots.

He studied hard and also enjoyed frequent trips to Barton Springs. Part of our family lore is that he also enjoyed "bathing" in the Littlefield Fountain at UT, along with some buddies, perhaps after getting marinated at Scholz Garten. Campus police were not particularly pleased, but, back then, well, "boys would be boys."

In 1941, still just eighteen, Everett Carlson was savoring the sensational Longhorn football season.

As a kid, he had grown up worshipping the greats of the early '30s, especially Ernie Koy and Harrison Stafford. But this UT team was, for the first time ever, ranked number one in the nation. But five days later, the team that had adorned the cover of LIFE magazine and averaged 38 points per outing was tied, 7-7, by Baylor. A 14-7 loss to TCU quickly followed. The Rose Bowl bid had gone-a-wastin', so the now tenth-ranked Horns took it out on the second-ranked Aggies, 23-0, in College Station. On December sixth, the vengeful Steers roasted a 5-4 Oregon Ducks team by the astounding count of 71-7. It was a helluva team, led by All-American end Mal Kutner, along with other stars such as FB Pete Layden, HB Jack Crain, and Chal Daniel, the standout guard.

The next day, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. The world had changed, and the U.S. was no longer on the sidelines of war. Everett Carlson, like many college students, signed up for service. He chose the Marine Corps. College was on hold.

Daddy was eventually stationed in the Philippines. Like most of the men of The Greatest Generation, he later shrugged off any plaudits about having served. "Don't complain, don't explain," was the credo of the era. Nobody considered himself a hero. All I remember really hearing as a kid were some funny but brutal stories concerning Drill Instructors at boot camp, then tales of nimble Filipinos, shinnying up trees to knock down coconuts for the American troops. Decades later, my nephews, Wade and Chad, Daddy's grandsons, got a plethora of amusing stories out of him.

My dad was one of the millions who survived the war, returning home to meet a pretty business college student from Lometa named Thala Jewel Ivy, and they married in 1946. A year later, EJ Carlson had his UT degree and became a petroleum geologist. Three kids came along -- I was the last -- and then, in the late '50s, Daddy boldly went into business for himself as an independent oilman. We moved from a two-bedroom home to a new four-bedroom place. Karen, Diana, and I each had our own rooms!

Besides fueling my Longhorn spirit, Daddy used persuasiveness to get me to try food I was too dumb to like yet, such as steak and barbecued chicken. "It's what Stan the Man Musial eats," he would tell me.

As a Son of the South, my Dad had grown up following the Cardinals on KMOX Radio when St. Louis was the southernmost outpost in major league ball.

Soon, I was in Little League, and Daddy was one of my coaches all four years. We talked incessantly about strategy and every nuance of baseball. I was mesmerized, just like I was when our family began attending three home football games per season at Memorial Stadium. We always got there early to watch all the warmups and see Bevo and the Longhorn Band make grand entrances. And we always stayed till the gun sounded, so we could see the tower magically turn orange after night games and so I could vault over the rails of the north end zone and pat players' sweaty jerseys and get autographs. The life.

For all the other games, we were watching on TV (twice a year plus the bowl) or listened to the radio. The games were vividly brought to life via radio, thanks to the magic of colorful broadcasters such as Kern Tips and, later, Connie Alexander. We listened raptly while Tommy Ford ran over an SMU defender "like a steamroller over a fortune cookie." Or when one of the Texas defensive backs had a would-be Aggie receiver "covered like white on rice."

Daddy and I took many road trips over the years. He loved South Texas, where most of his oil & gas work was centered. He taught our family how to go crabbing down at Indianola, and he and I once hauled in 141 blue crabs, some for gumbo, some to later toss back. He loved the forests of East Texas. En route, he enjoyed hitting Lockhart and Elgin, his hometown, for smoked meats. At the original Southside Market, we would weigh in on the big scales out by the meat counter, then stroll through the sawdust in the back part of the store, eager to get "hot guts," the town's special sausage. On the way out, we'd see how much weight we had piled on.

My Dad, probably like yours, didn't exude toughness. No tough guy veneer. He just exemplified toughness, as did Momma, as did so many of their peers who grew up having to stick to it in life and everything it brought. Within our family circle and among others, Daddy was generally quiet but pleasant. He did like to tell a few stories and jokes, and, boy, he could cuss. He reserved most of his ire for traffic, inanimate objects such as stodgy lawnmowers and tools, and certain politicians. At our supper table/political roundtable, LBJ was known simply as "that big-eared SOB."

When I went off to college, Daddy never tried to influence my choice of majors. I'm pretty certain he knew I had inherited none of his expertise in math and science. But he told me this.

"You can choose a career that'll bring in a decent paycheck and probably not like the work much."

That, he told me, is what he had done.

"Or," Daddy said, "you can pick something you like and probably not earn much money."

I did not take it as a pessimistic view. For me, it turned out to be prophetic. I went into broadcasting and other forms of writing, then ended up also teaching. Never really felt like work. Hardly made a nickel, either. But it's been fun.

He had his share of problems. He and Momma drank too much. So they quit drinking one day when I was in eighth grade, started attending meetings, and, amazingly, never drank another drop.

They were chain smokers. But in their sixties, they found a way to quit.

Daddy periodically battled depression. And he fought his way through it. Late in his life, because of poor circulation and perhaps the chronic problems with "jungle rot" in his feet during his time in the Philippines, he was forced to have a leg amputated. He was stoic in spite of becoming increasingly dependent upon assistance from health workers.

It's been almost twenty years since my Dad passed away one July afternoon. Obviously, I think of him often. My sister, Diana, and I, the survivors since Daddy, Momma, and Karen passed, like to regale each other with stories and oft-told jokes that still make us laugh with them all.

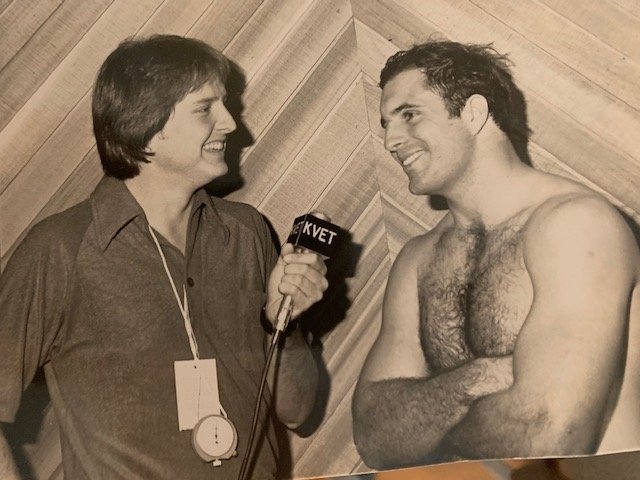

Many decades ago, my parents grew especially proud when I had the good fortune to, just one year out of college, get hired as an Austin radio sportscaster. I hosted the post-game Longhorn Locker Room Show on KVET.

I can still recall being on the field before the start of one of my first games. When the Longhorn Band roared past me on the track, their brass reverberating through my soul on the always-rousing "March Grandioso," I was surprised to have to hold tears back, just thinking of all the times I had sat in the stands with Daddy, soaking it all in. Now, he and Momma were at home in San Antonio, listening to the radio. And I was actually here, doing a job.

To this day, that song always always induces chill bumps. "March Grandioso" is never one to disappoint.

Just like Daddy and my memories of him.