Longhorn author Jenna McEachern say the Cotton Bowl tunnel, “is the “last mile” of college football- a dark, narrow tunnel leading players toward the daylight, toward the frenzy, toward the moment of truth.

A link to the tunnel experience October 2022

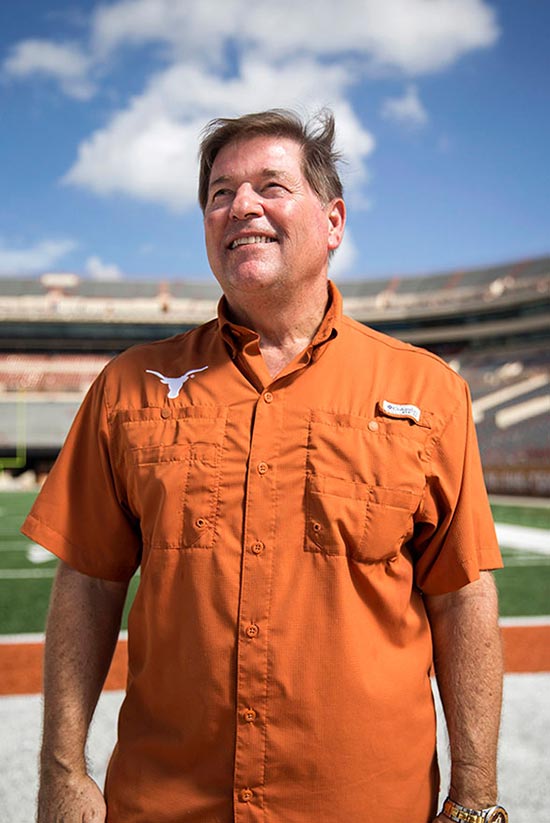

10.12.2012 | Football Bill Little commentary: Run it again

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

It hasn't changed. The fabled "tunnel" from whence the players and coaches enter remains the same, as if waiting for the entrance of the gladiators into the coliseum.

The players, however, will remember the tunnel, the arena, and the unequalled atmosphere. …..They know that in practice you can "run it again." But in this game, you do not get "do-overs." It is an extended moment in time, where the re-runs come on television, and the memories stay for a life time.

David McWilliams says that “running down the ramp at the Cotton Bowl, that’s a larger-than-life experience that sticks with every player evet to take part in the border war.” McWilliams continues “when you walk onto that field there is a force field of electricity.” “You actually visualize streams of electrical current coming of the field. You feel like you’re walking a foot off the ground. “

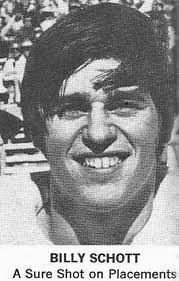

“Billy Schott, BS ‘83, a former Longhorn placekicker and wide receiver, remembers his final journey through the Cotton Bowl tunnel as a player. Alcalde magazine October 9th, 2014 reprinted his memories of the “Tunnel”.

”

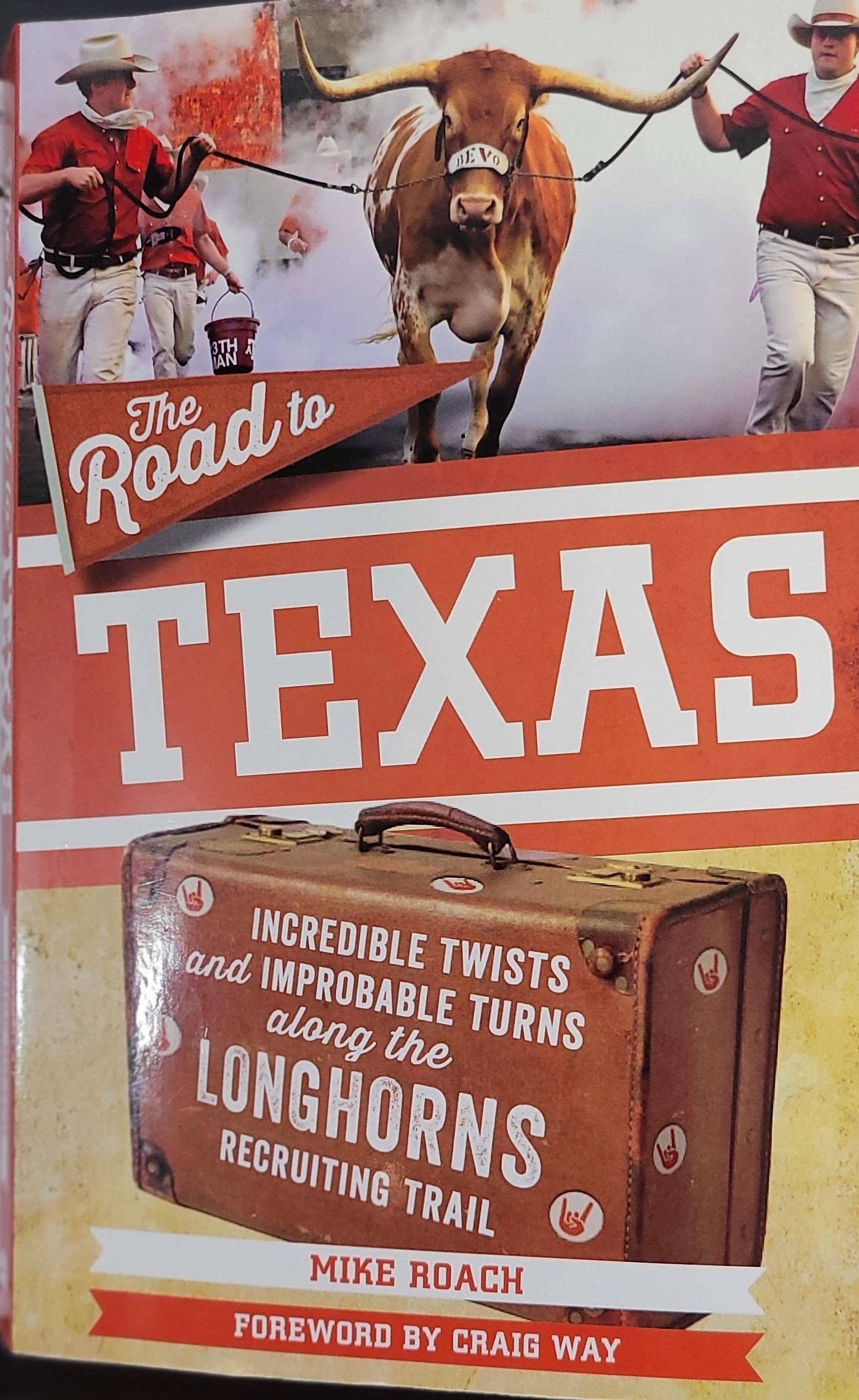

Below is a great article by Billy Schott that captures the OU game from the players perspective. DKR played in the series as a OU player and the Texas Coach. His comment in the book "Darrell Royal Dance With Who Brung Ya " by Mike Jones and edited by Dan Jenkins Jones adds even more perspective to Billy's great article. DKR says "The thing about the Texas-OU game - then and in all the ones I was involved in - was that both sides went on the field knowing they were going to get their fanny kicked." "The only question was going to be who won. Win or lose the players knew they would "get beaten and bruised."

Billy Schott's article follows

When you’re given the final word from the TV guy to leave the locker room and head down the short flight of steps to the top of the tunnel, you step out into a surreal, confusing world of childish taunts and many an inverted Hook ’em being hurled from the walkway above. Stadium security personnel in cheap windbreakers and several members of the Dallas Police Department man the long, tarp-covered gate behind you. You recognize a couple of the motorcycle cops that led the police escort through the streets of Dallas a couple of hours ago; an officer smiles as he gives you a quick salute and a Hook ’em. You return the salute and mouth a quick “Thank you” to the officer.

You’re told by the TV guy to wait at the top of the ramp. There’s no breeze—it’s hot.

Someone steps out of a black limo just outside the gate and is quickly escorted by Texas DPS troopers through the gathering and hurried down the ramp. Must be the governor or a senator or Willie—you can’t really see over the glare of all the glistening white helmets shining in the October sunshine.

The smell of diesel fumes, horse crap, and fried food wafts through the air, mingling with the sulfur smell of residue from the RUF/NEKS’ shotguns and Smokey’s pregame cannon shots. You can always smell the State Fair.

The ticketless, orange-clad well-wishers behind the chainlink gate, trying to get a quick look from a player or coach, are the only friendly voices you hear at that end of the Cotton Bowl.

“Get after ’em, Darrell!”

“Go Horns!”

“Anybody got a ticket?!”

“Can I have your chinstrap?”

No “OU Sucks” chants—these are the days before that sentiment became the norm.

Strangely, above the yelling, the dull din of bus engines, police motorcycles, and the screaming siren from a ride over on the midway, you can hear the clicking of the candy-wrapping machines in the salt water taffy booth just across the walkway beyond the gate.

You’ve been taught to keep your focus, to look toward the light at the bottom of the tunnel as you move slowly downhill. You’re wedged so tightly together that your feet are barely touching the ribbed, dirty concrete below. It’s like you’re slowly floating down the ramp suspended among your fellow team members. You’re in the shade of the tunnel now, beneath the stomping, screaming Sooner fans in the south end of the stadium. It’s cooler, but you’re having trouble catching your breath.

The Opponent at the tunnel

You can’t help but steal a glance at your opponents as they assemble and begin to move down the ramp on the opposite side. You’ve seen them all through pregame warmups, exchanged subdued good luck wishes to a misguided former high school teammate who wandered across the Red River, but suddenly, this instant is etched forever in your mind. The crimson helmets with the white interlocked “OU” really piss you off at this moment and the bile rises in the back of your throat. You feel like you might lose your steak and scrambled eggs you ate four hours before in the quiet banquet room at the Hilton Inn. You don’t want to puke on your facemask—or on your teammate’s back.

Instead of letting the remnants of your pregame meal fly, you choke it back and begin to yell out an unintelligible guttural sound. Your teammates join in and the sound reverberates in your helmet. Your mouth is dry, your chest is pounding. All of a sudden, your uniform is too tight. A huge groundswell of noise engulfs you as you move closer to the light, louder and louder. You’re glad you have your helmet on, not because you think that one of those over-served, jeering Okies will lob a half-eaten Fletcher’s Corny Dog at you, but you feel secure and impervious when you manage to reach your hand up and snap your chinstrap snugly as you move into the sunlight at the bottom of the ramp. You realize then how much you’ve been sweating as the swirling breeze on the floor of the stadium finally gets to the back of your neck and cools you ever so slightly.

Bryan Miller in the tunnel with a Sooner by his side

The roaring sound echoing in your helmet reaches a crescendo as the TV guy tries to hold back your screaming, snarling teammates. You look around and the sudden reality hits you: This is it. This is the last time you’ll ever experience this feeling as a player in what you have grown up knowing to be the greatest football contest in the universe. You may get a chance to walk the ramp again, but not wearing this uniform, with these guys, against those guys.

Tears well in your eyes, a huge lump rises in your throat as you begin to hear curses hurled at the TV guy to let you go, just let us run out on that crappy turf one more time. You hear the TV guy yell something about the World Series game being nearly over and to hold on for just one more minute, and one of your larger teammates instructs the TV guy to perform a physically impossible task with a baseball.

You and your teammates surge forward, frenzied and frothing. You look toward Coach Royal, who has appeared just to your left—he looks to be alone in his thoughts. His jaw is set. He has to hear the taunts of “Traitor!” directed his way. You feel more contempt for the red-clad fans leering over the tunnel walls as they wave red and white pom-poms at your coach’s face. You wish the woman would fall over the wall as she screams, “Darrell, you ain’t sheeyit!”

He is perturbed at the delay. He gives a simple nod and the human dam breaks. The TV guy is left to fend for himself. He may have been trampled, but you don’t really care at this point. Smokey sounds out a huge cannon blast, a perfect smoke circle rises above the sweltering field. You imagine a football sailing right through the center of the white smoke circle as you see it emblazoned against the clear, blue North Texas sky. You hear the band playing “Texas Fight” at what seems like an impossibly fast tempo and an ungodly loud volume in your helmet. You run. Your teammates are jumping all over you. You may cry.

You aren’t alone.

The swelling noise is louder than ever and you get to run out into that sunlight one last time. You’ll never get to feel this way again.

"Run out into that sunlight one last time."

Click on site below for more on Billy Schott

In the book Game of My Life, Donnie Little shares his experience walking down the tunnel. He said, “Going down the tunnel definitely gives you goosebumps. You’ve got people on one side, screaming and calling you the worst names, and the other half is cheering for you. You definitely want to show up. You didn’t want to have a lackluster performance. If you could play every game with the kind of intensity you have against Oklahoma, you’d be an All-American. …. On a good day, I could throw the ball 60 yards. When you come through the tunnel and you are out there warming up, I could have thrown it 70 yards.”

In What it Means to be a Longhorn by Bill Little, Coach Pat Patterson says to Doug English about the tunnel, " No place for a timid man, is it?"

In 100 Things........ Jenna McEachern states that Pat Culpepper likened smiling to the cameras during pre-game introductions to "laughing before you land at Iwo Jima."

In What it Means to be a Longhorn by Bill Little, Coach Pat Patterson says to Doug English about the tunnel, " No place for a timid man, is it?"

In 100 Things........ Jenna McEachern states that Pat Culpepper likened smiling to the cameras during pre-game introductions to "laughing before you land at Iwo Jima."

Billy Schott's accomplishments are a reminder to all Longhorns that In sports and far beyond, his contributions to Longhorn heritage shape the present and empower the future.

Not part of Billy Schott's article, but a good story about the 2018 tunnel experience was told by Aaron Williams. Aaron recounts that when the buses arrive, they enter through the fair, passing through a crowd. Fans are already fighting before they even make it to the locker room. Both locker rooms share the tunnel, so you face the opposing team when you come out. It gets intense in the tunnel. There have been countless arguments and fights in that tunnel.