The Good Side of Joe Don Looney, as told by Longhorn Chuck Taylor

Joe was a dear friend. His folks, Don & Dorothy, were 'bridge partners' with my Mom and dad in FW. His best friend in FW was my ex-brother-in-law, with whom he went to Austin/UT. Joe lived in Austin for a brief time during the summer/fall of '85.

Lyle Blackwood

L-R Joe Don, Chuck Taylor (me), Joe Bednarski (aka pro wrestler, Ivan Putski).

Transitioning back from India, he weighed about 150lbs. I introduced him to Steve Helton, the owner of Big Steve's Gym (where I worked out), and we became workout partners. Big Steve, Joe, Joe Bednarski (aka Ivan Putski), and Dolphin great Lyle Blackwood would work out

together. Joe absolutely loved being with these guys. The stories told were incredible. I saw Joe put up 225 on the seated military press in three sets, 12 reps at his weight of 150ish. He just smiled, looked at me, and said, 'Muscle never forgets.'’ At first, you couldn't get him to talk about football, but once he knew you and was comfortable, you couldn't get him to stop talking about the ball.

He loved high school football. One night, he came by the house and talked me into going to the Goldthwaite vs Runge State 1-A Championship game in Georgetown. He wanted to go to Waco the next day and end up that evening at Cowboy Stadium. He claimed we could watch all the State Championship games in two days. Johnny Unitas told me he'd have to return to Jim Brown to find a better running back. Bud Wilkinson literally used me as a sounding board to his regrets about how Joe was treated. Joe had a genius IQ. Incredibly inquisitive and with a fantastic sense of humor. He was about 20 years ahead of his time. He was John Riggins before John Riggins. He graciously allowed me to videotape his life memories that summer. Truly, his life was stranger than fiction. He had regrets and was remorseful at times. He loved his daughter and loved the game of football. It seems just about everyone has a JDL story. I knew Joe to be a really good guy who had finally found his peace...

Chuck Taylor says “Unitas rank Joe second only to Jim Brown as far as a pure running back talent. Bill Harwell and Monte Williams were part of my Team that interviewed Johnny U at his home in Baltimore. He was quite interested in knowing what happened to JD. Unitas shows me the injury location that ended his HOF career in the attached photo.

For me, it was an incredible life experience. J. Brent Clark contacted me wanting deep insight into his book. I was very vague with my answers. I didn't know him or how his book would portray Joe. I can honestly tell you that my hours of tape with Joe will never be seen. Yes, his life was full of chaos, disappointments, and heartbreak...How he was raised was significant in defining him and his choices. We all have our share of do-overs we'd like to have. Joe was no exception. In 1963 a 230-pound white guy who could run a 9.6 100-yard dash and beat Gayle Sayers in the 60-yard indoor, and bench press a house was a freak of nature. Like I said, he was just a life force that, unfortunately, operated in the wrong decade...

The 1963 Texas-O.U. Game and Joe Don Looney

Superman Meets Kryptonite

Looney “I wouldn’t sweat Texas like I sweated Southern Cal” . I don’t think Texas can move much against us.”

Joe Don was not a mainstream athlete with a team mentality. He was one of the first rebellious athletes of the 1960s. One who was outspoken, non-traditional, questioned authority, and rejected dress codes.

His self-absorbed life decisions resulted in harmful self-inflicting behaviors and ended with the ultimate self-infliction - death by motorcycle.

Many football fans and players were repulsed by his lack of respect, arrogant attitude, and condescending remarks about the Longhorns. In particular, Longhorn Bobby Gamblin detested Joe Don Looney.

Bobby Gamblin was so upset with some of Joe Don's comments that he hollered at Looney during the pre-game of the 1963 Texas O.U. game, "Hey Looney, Get Off The Field, You Creep. You're Killin," The Grass."

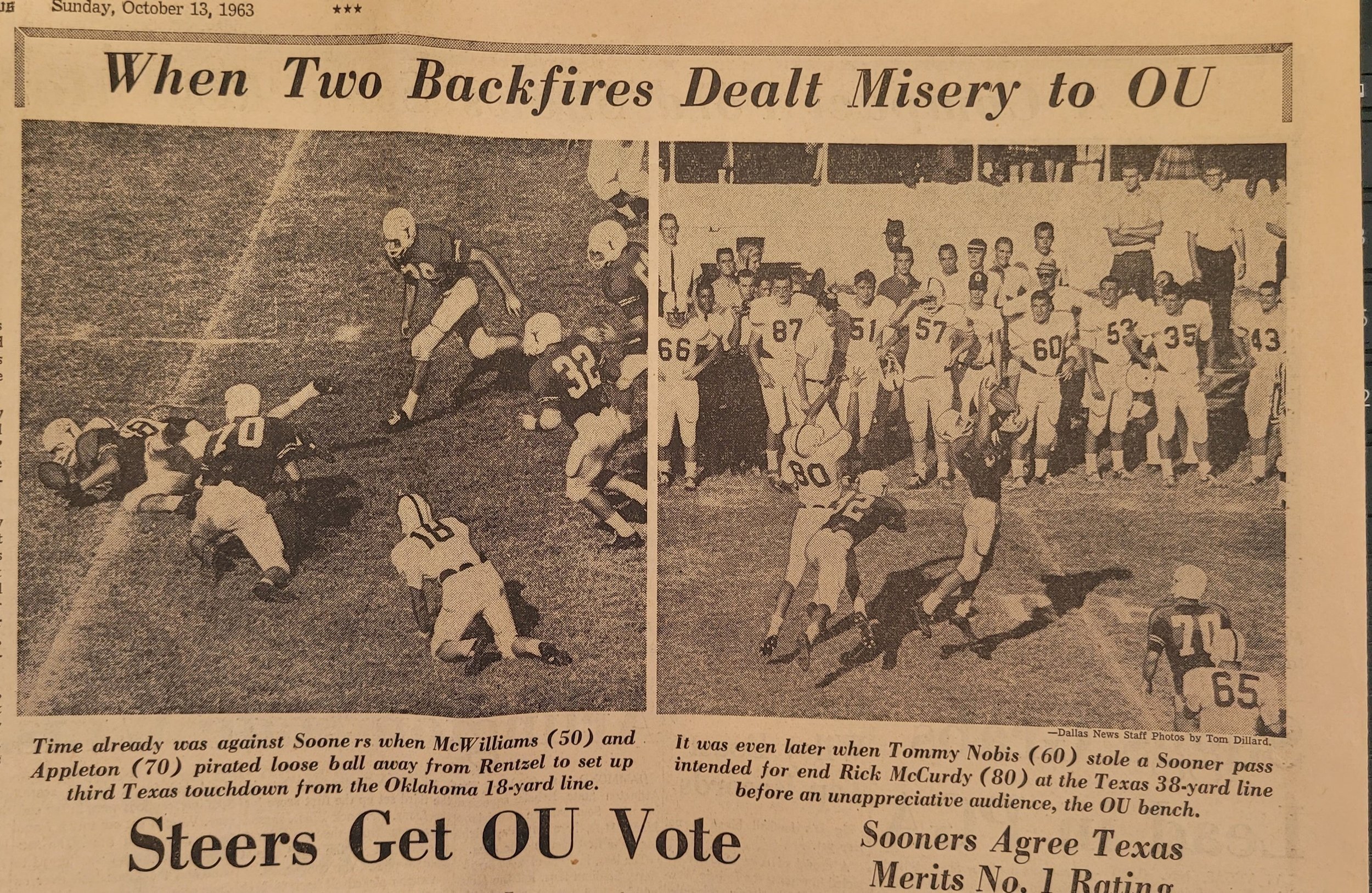

In 1963, Superman Joe Don Looney was exposed to Longhorn kryptonite—the Superteam defense led by Longhorn Tommy Nobis. Texas won the game. After Texas exposed Joe Don’s weakness, O.U. released the Superman grass killer.

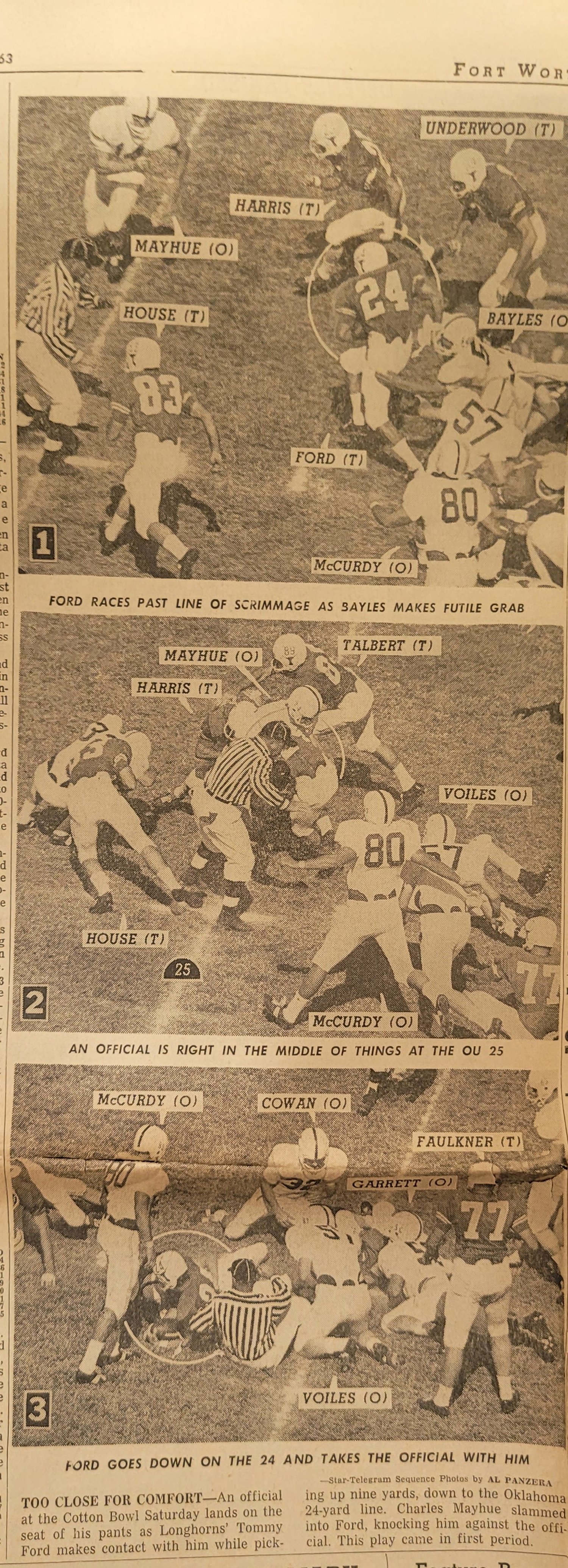

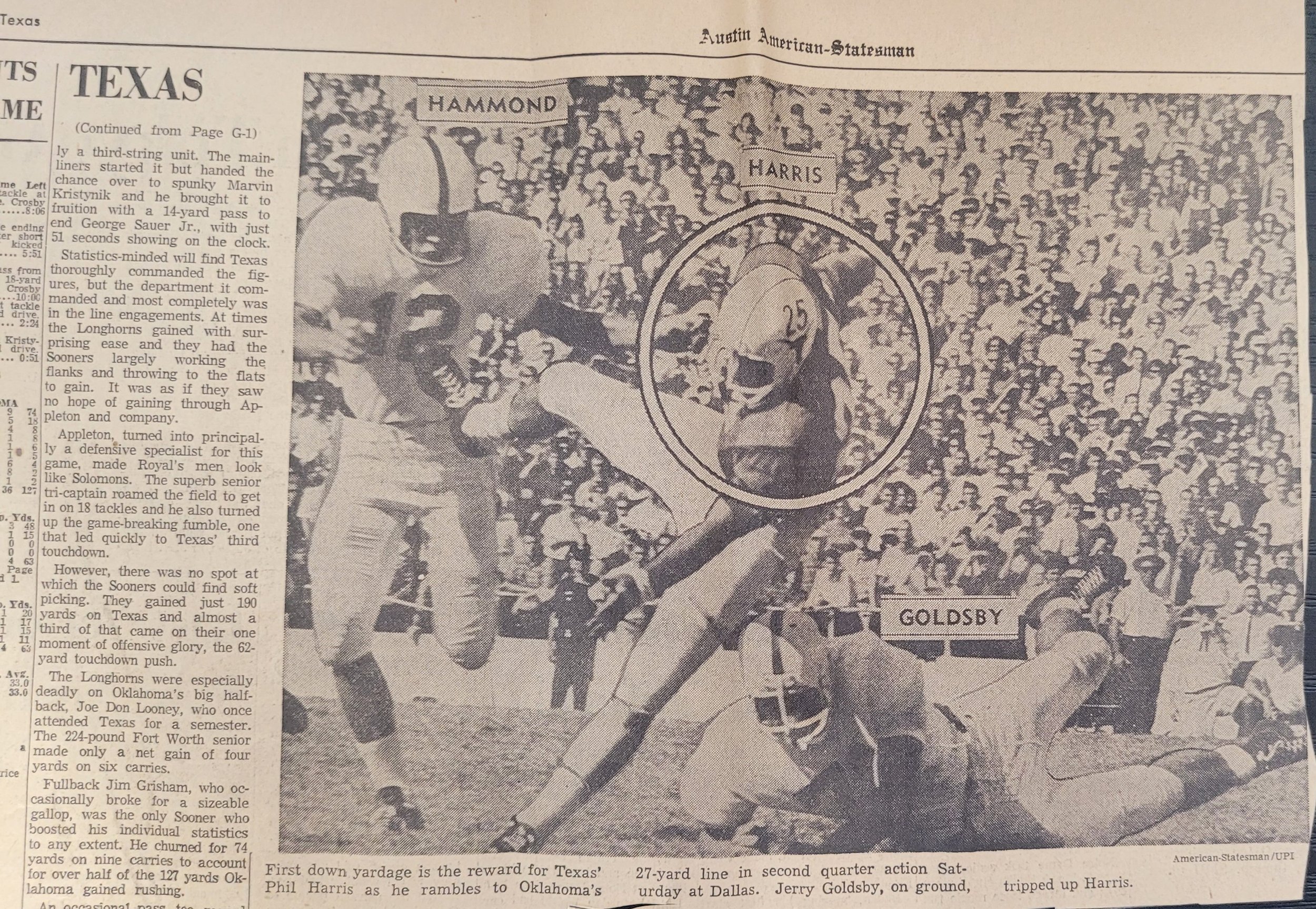

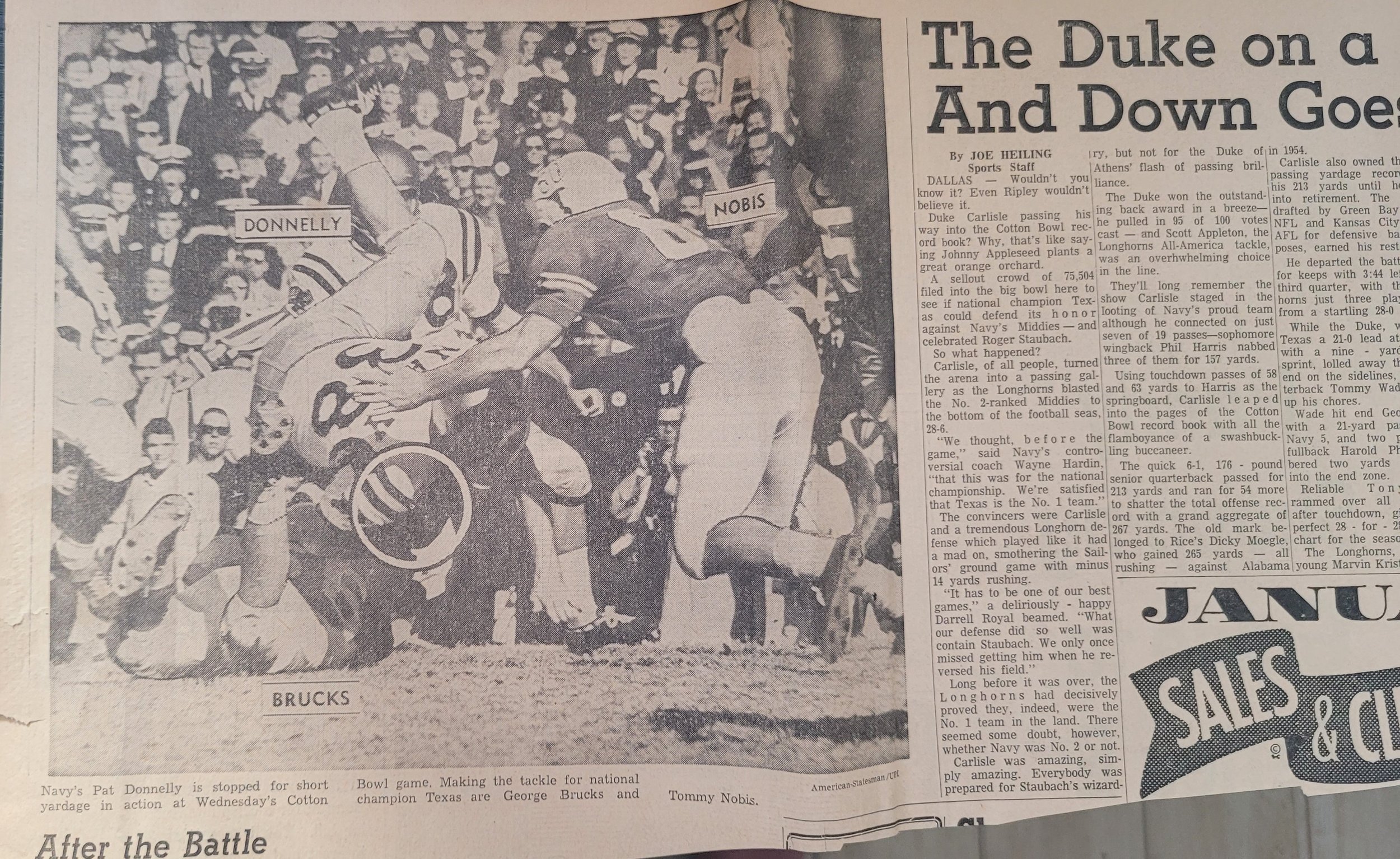

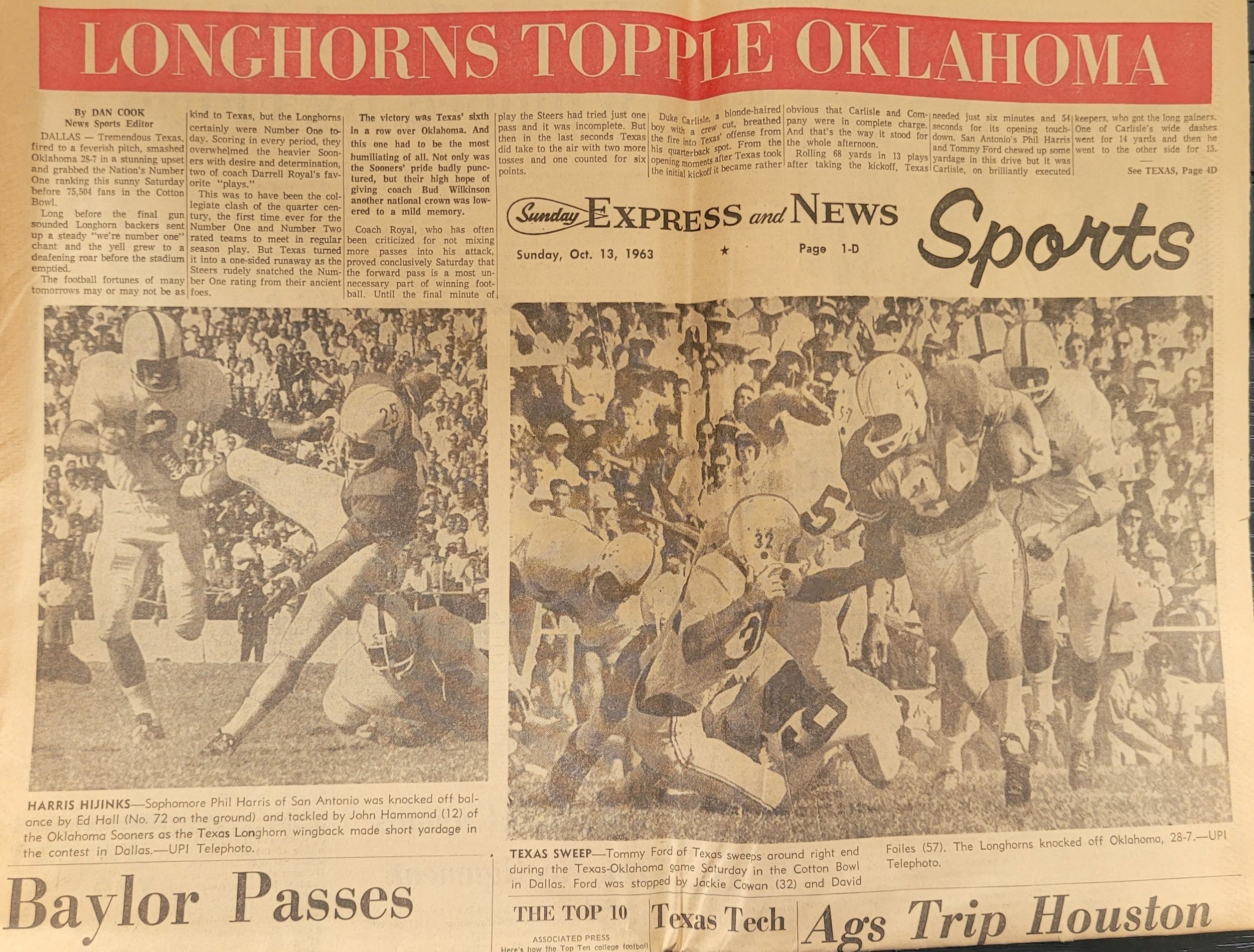

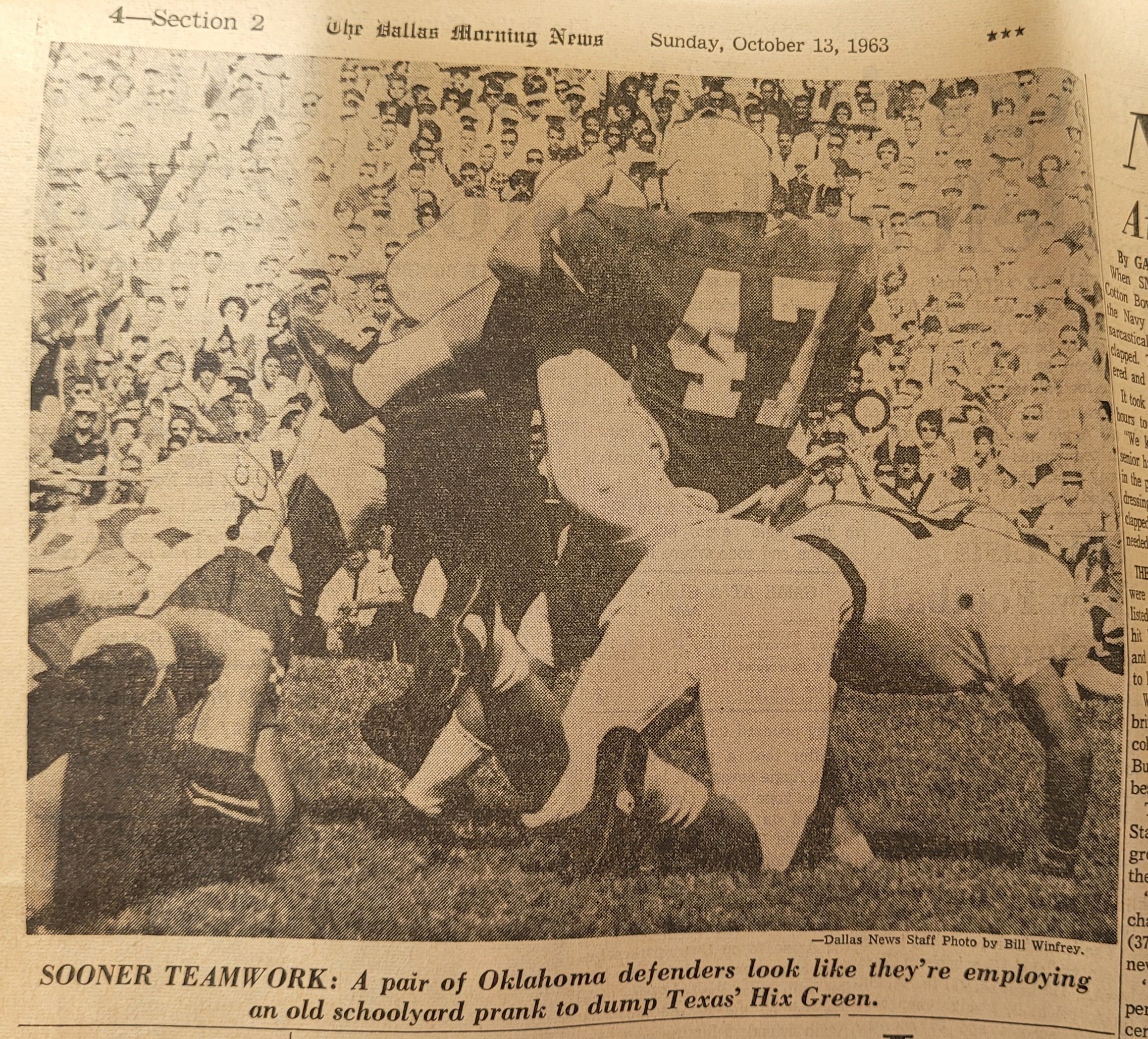

Below is a slide show presentation of the 1963 Texas-O.U. game .

TLSN is a 501 (c) (3) composed of educational and charitable components. The TLSN website is a free public site building bridges linking past, present, and future Longhorns.

Educational “fair use of articles” guidelines apply to the material used by educational institutions for educational purposes. Examples of "educational institutions" include K-12 schools, colleges, and universities. Libraries, museums, hospitals, and

“other nonprofit institutions are also considered educational institutions under most educational fair use guidelines when they engage in nonprofit instructional, research, or scholarly activities for educational purposes.

The Bad Side of Joe Don Looney as told by professional writers

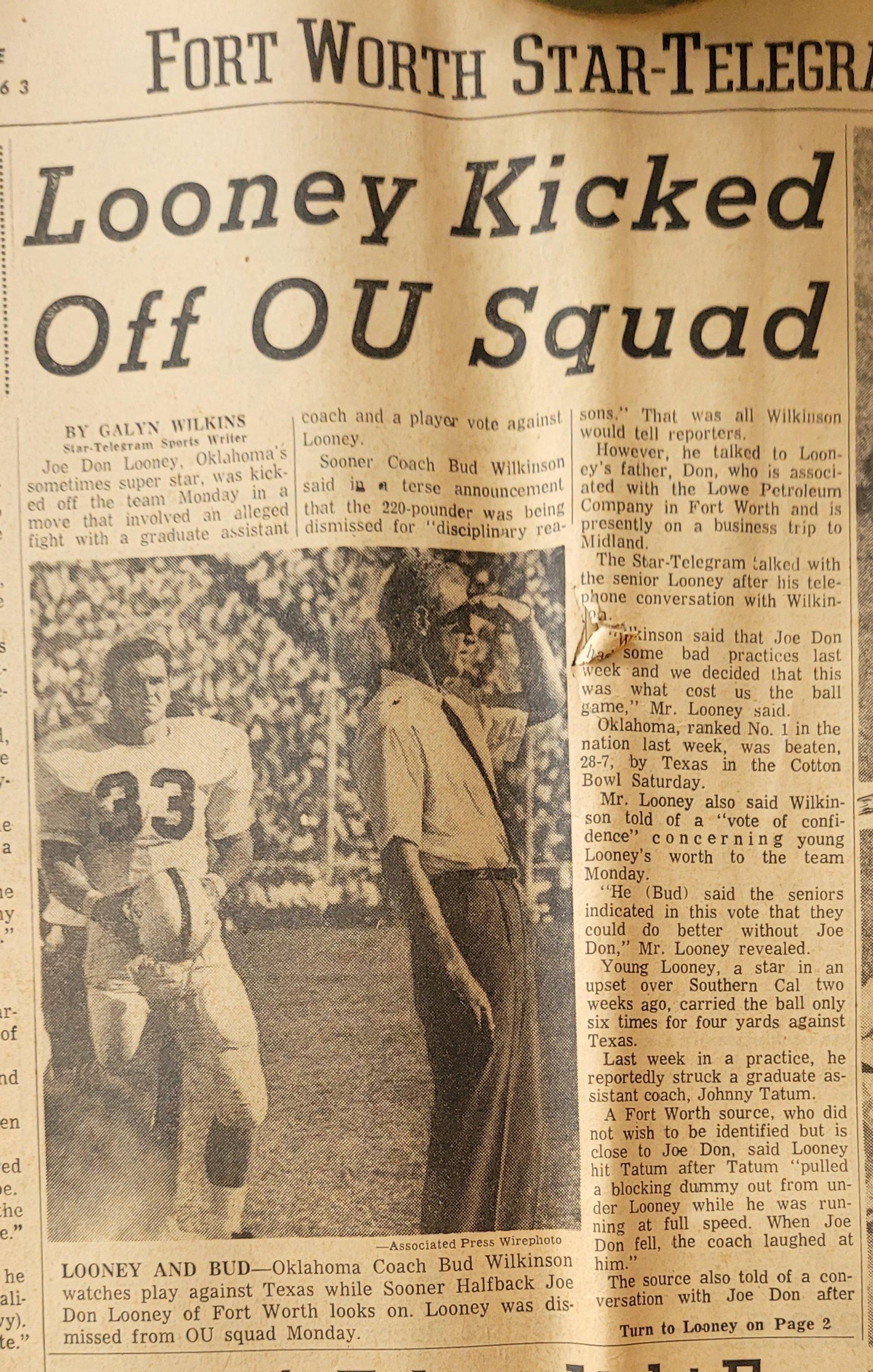

From Wikipedia - "Looney received four Fs and one D. Looney in his first semester at Texas. " Jeff Olsen states that "JDL wasn’t a DKR recruit. He had considered running track and showed up for a practice or two but instead spent the fall rushing Kappa Sigma till the IFC told them to ditch him. " The book “Third Down and Forever” by J. Brent Clark chronicles Joe Don’s unique life. There’s also a shorter read by SI entitled “The Greatest Player Who Never Was. He left Texas and enrolled at (TCU). He was eventually kicked out of that school and transferred to Cameron Junior College. He set a punting record in 1961 as his team won the junior college national championship. He set a punting record in the 1961 Junior Rose Bowl, as his team won the junior college national championship. He made All-American with the University of Oklahoma in 1962, leading them to the Big Eight Conference championship. He played in only three games in 1963. Head coach Bud Wilkinson kicked him off the team after the Texas game.

“The Greatest Player Who Never Was” was written by Andy Benoit for Sports illustrated june 21, 2017

Joe Don Looney came to the NFL as a generational talent, a first-round pick despite being dismissed from his college team. He left a legacy of frustrated coaches, barroom brawls, and constant disappointment. And when it was over, he embarked on a post-football life like no other.

“If you want a messenger boy, call Western Union.” —Running back Joe Don Looney said to head coach Harry Gilmer after Gilmer asked him to send in a play from the sidelines during what would be among Looney’s final moments as a Detroit Lion.

He turned pro under comparisons to Jim Brown and, nearly 30 years later, was invoked by Don Shula as an early era form of Herschel Walker. But Looney’s career lasted just five seasons. He played for that many teams, driving all of his coaches crazy. He was a fascination of the media.

You might expect Joe Don Looney’s story to be that of brazen, perhaps even heroic, individualism. A counter-culture icon stuck in an era of conformity. A different cat who walked away from the glories of pro football in search of deeper meaning.

But zoom in closer, break it down into pieces and what you see is a clear illustration for why he was once characterized by Bill Walsh as a “coach killer.” And why longtime NFL Films president Steve Sabol called him “the most uncoachable player in NFL history.”

For the rest of Joe Don’s Sports Illustrated story, visit “The Greatest Player Who Never Was,” written by Andy Benoit for Sports illustrated June 21, 2017

You can’t zoom in on Looney without reading J. Brent Clark’s biography on him, 3rd Down and Forever.

Here are a few comments that Brent Clark makes about Looney.

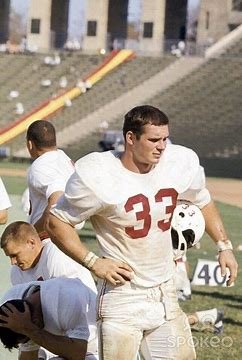

Looney’s time in Norman would be a harbinger for the rest of his football career. A sensational playmaker, he drew national attention after his spectacular performance versus Syracuse was featured in the Sunday edition of The New York Times. And yet, his playing time was sporadic. Looney was disenchanted with the culture at Oklahoma. He hated that athletes lived separately from the other students. He didn’t like eating at the athletic training table. He felt stigmatized as a JUCO transfer. He disdained Wilkinson’s authoritative system.

“The cliché is, ‘When the coach says, Jump! the question is, How high?’” says Michael MacCambridge, author of America’s Game, the leading record of pro football history. “Looney was in this group of players who were asking, Why should I jump? Why do I need to jump now? What is me jumping going to do for the cause? Why do I have to jump during practice when I can jump during the game?”

Still, Looney’s talent was unmistakable. “Looney was fantastic at Oklahoma,” says football historian T.J. Troup. “Just on physical ability he could have been a good [NFL] player.”

Looney was ahead of his time in some ways, especially when it came to training, an elaborate regimen centered around then-foreign endeavors like stretching and taking vitamins. An avid weightlifter, he journeyed to Alvin Roy’s gym in Baton Rouge in the summer of 1963. “Alvin Roy of course brought steroids into pro football in the early ’60s with the Chargers,” says MacCambridge.

In 3rd Down and Forever, Looney’s close friend and teammate, John Flynn, said, “I would say [Looney’s steroid use] was obvious from looking at him. There had never been anything bad said about them. It wasn’t an issue whether it was legal or not. There was certainly no problem with taking them. It wasn’t anything about what they know about them today.”

The concerns about Looney’s newfound bulk was that it would impact his speed. But Looney insisted—and then proved—that it didn’t. He was an All-America in 1962, but the conflict with Wilkinson came to a head less than a month into the 1963 season. The Sooners fell behind 21-0 against Texas and Looney, who ultimately rushed for four yards on six carries that day, was downtrodden. Accounts of what happened vary. Some thought Looney simply got stymied by Longhorns middle linebacker Tommy Nobis, who was assigned to follow Looney much of the game. Others were less sure. “Joe Don quit,” former teammate Ronnie Fletcher told Clark. “It’s that simple. Just didn’t put any effort out.”

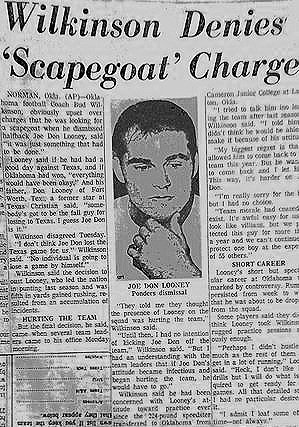

Wilkinson had had enough. A few days later, he sent team co-captain John Garrett to inform Looney that he was off the team. There were reports that Looney had been dismissed because he hit an assistant coach. These were easily believed; around Norman, Looney was a known barroom brawler. But years later, in Clark’s biography, that assistant, Johnny Tatum, refuted this. “I heard the news on the radio,” Tatum recalled. “The announcer said ‘Looney was dismissed from the team for hitting assistant coach Johnny Tatum.’ No one ever called me in and talked to me about the matter. I really resented [the staff] using me as an excuse to get rid of Joe Don. Nothing ever happened between Joe Don and me.”

Thom Loverro with The Washington Times - Sunday, July 3, 2016 wrote about Looney.

ANALYSIS/OPINION

Thom Loverno

He was a very talented and powerful 6-foot-1, 230-pound running back, and his talent tantalized coaches who believed they could fix him.

In Washington in 1966, Otto Graham was one of those coaches.

Looney lasted two seasons in Washington and it was Sam Huff’s job to try to keep him in line. He talked to me about that in an interview for my book, “Hail Victory: An Oral History of the Washington Redskins”:

“Joe Don Looney was a potential talent nobody could tap. Otto called Sonny Jurgensen and Billy Kilmer down to his office and said, ‘We need a running back, and we have a chance to get Joe Don Looney.’ Sonny and Billy agreed that this was a bad idea and told him, ‘No, Otto, we have enough problems holding the players together here without him. Not one of those teams could control him. And he’s going to come here?’ The next day Joe Don was in a Redskins uniform.

For the rest of Thom Loverro’s article, visit tloverro@washingtontimes.com.

ONE THEY CALLED LOONEY

By Kevin Sherrington

For more great stories and insight of one of the best sports writers in the South West, click on Kevin Sherrington’s site.

November 22, 1988: This is an edited version by TLSN. For the full article, visit Kevin Sherrington’s website.

ALPINE, TEX. -- Joe Don Looney's funeral was a big one for this West Texas town of 6,000. More than 100 people filled the little chapel at Geeslin's Funeral Home, a peach adobe building that faces the jail across the street. A few people stood in the back of the chapel, and a handful spilled into the parlor off the side. They didn't have to stand for long. The service was over in 10 minutes.

They came to pay their respects to a man considered a maniac in most quarters. He was a man of contrast and conflict, full of questions and dissatisfied with most of the answers. He was both the gentle spirit that his teammates and coach from Cameron remember and the violent, rebellious cloth of his legend, 6 feet and 230 pounds of sprinter's speed bearing down hard on apparent destruction.

Joe Don Looney's stories are as fast as his 9.7 speed in the 100-yard dash. They are mean and usually capped with a stinging one-liner. They also are legion. For this side of him, the name Joe Don Looney could not have fit better.

Lew Johnson remembers vividly the play that made Looney famous. Johnson, a sportswriter in Lawton, Okla., who had covered Looney when he was at Cameron, was reporting on the 1962 Oklahoma-Syracuse game. Syracuse led 3-0, late in the game when Looney asked Sooners Coach Bud Wilkinson to put him in the game.

Looney told the Sooners' quarterback to give him the ball, and he would score. He did, first running over a Syracuse defensive end and then outrunning everyone else for a 60-yard touchdown. The Sooners won, 7-3, beginning what would be Wilkinson's last Big Eight championship season.

"Great game, pardner," Johnson said, grabbing his hand. "How do you like it here?"

"I wish Cameron had been a four-year school," Looney said. "Up here, I'm a number at a football factory. Down there, I was a person."

Looney often said Cameron's Leroy Montgomery was the only real coach he ever had.

Montgomery said the problems started when he enrolled at Oklahoma, a school that never before accepted junior college players.

"I told him I didn't think he should go to Oklahoma," Morrison said. "He asked me why, and I said, 'You're a juco {junior college} ballplayer, and you will start, and you're not going to be accepted by those people because of that.' "